“It is vital to give the kids some good attitudes”

– Jannik Hastrup

WeAnimate 2024-11-20 | wam#0052

This article was originally published in 2021 and is being republished without any updates. Please note that some information may no longer be current.

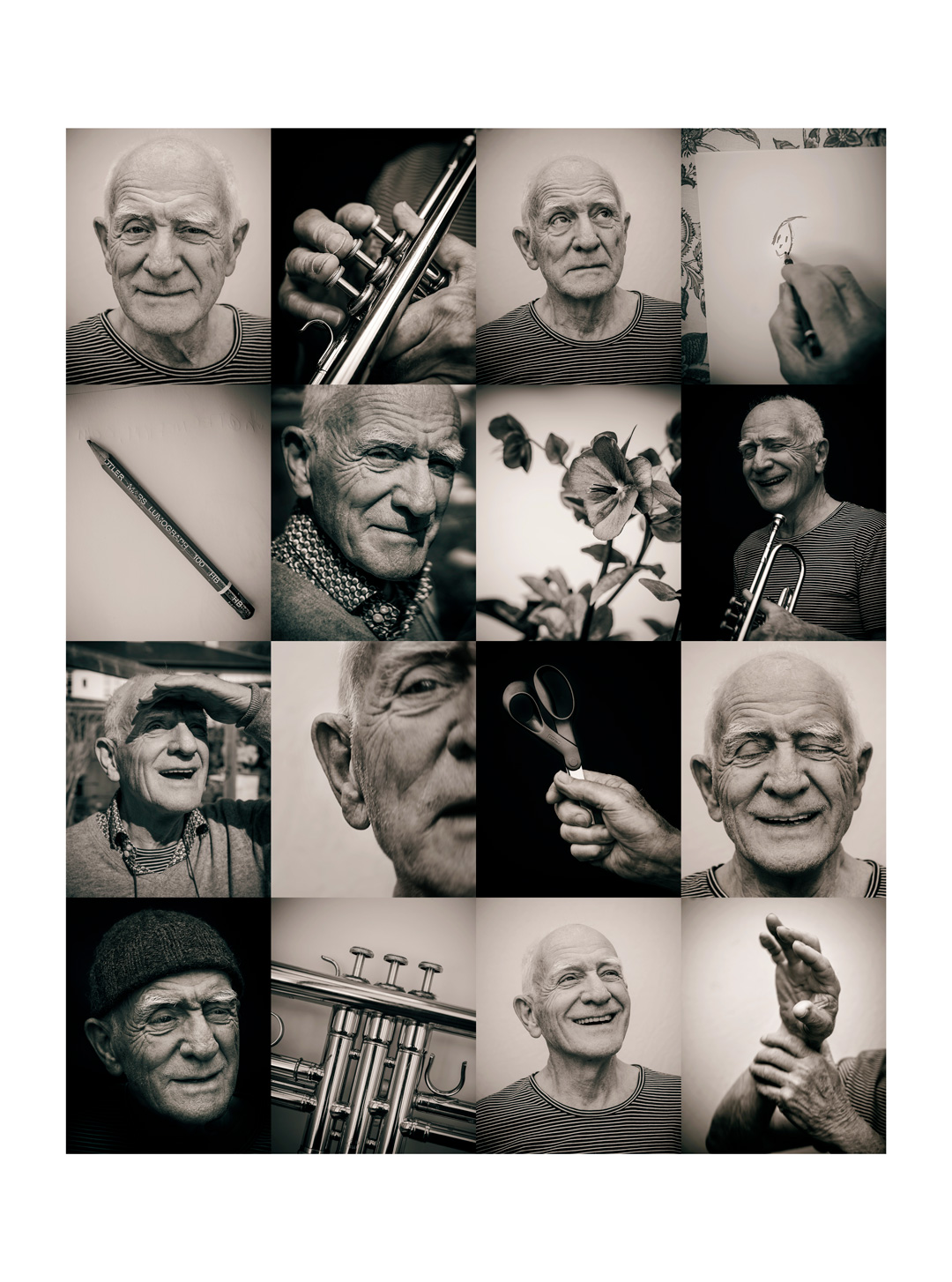

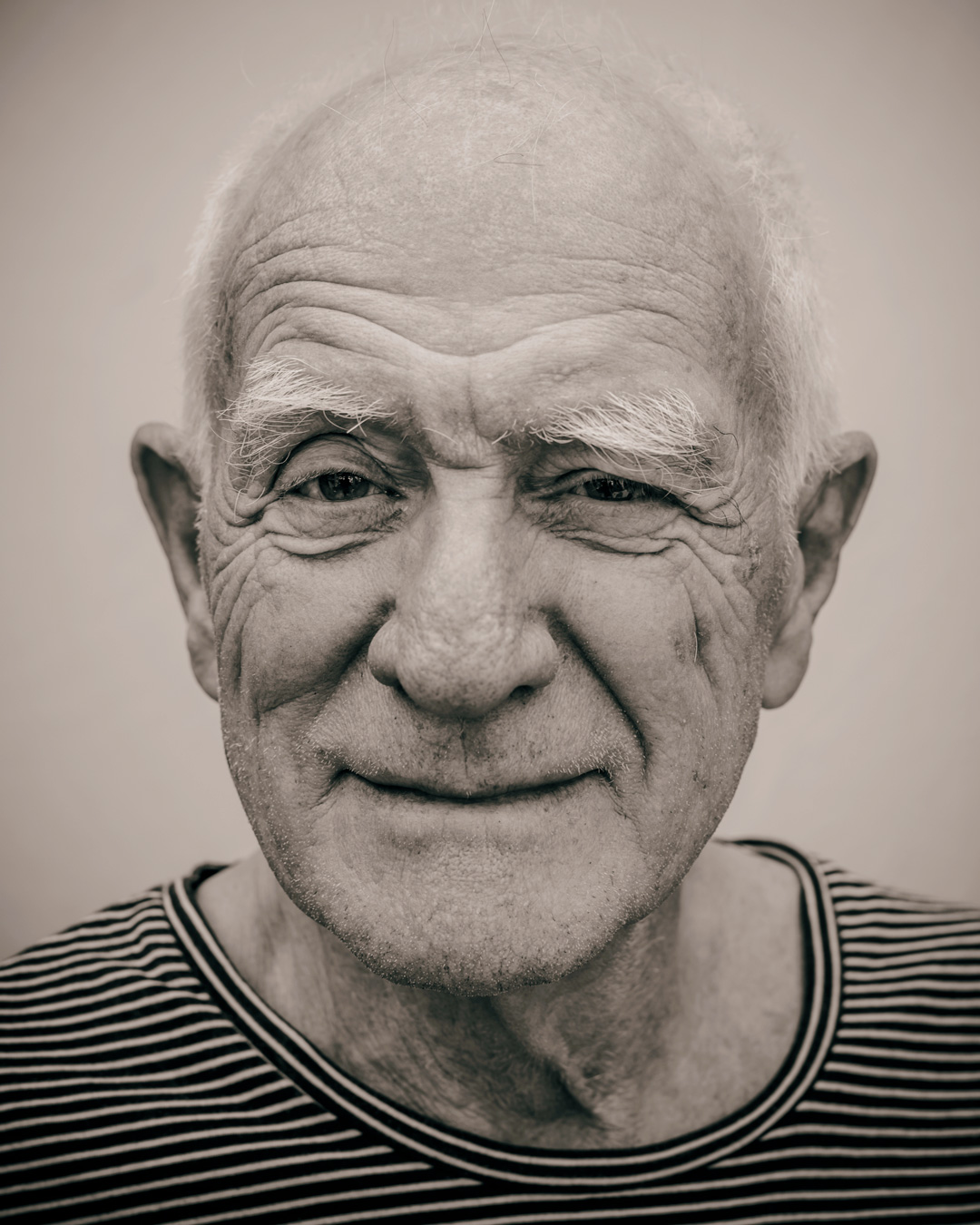

Through a lifetime’s work, animator and director Jannik Hastrup has stood up for the weak and at risk, with his buildable, poetic, funny, and dramatic stories for children – from Circleen, Benny’s Bathtub and Samson and Sally, to War of the Birds, HC Andersen and The Long Shadow, and The Boy Who Wanted to Be a Bear. Now, Hastrup has reached the age of 80, and he had initially retired. Not for long though, as a brand new Circleen film is on the horizon. There are still important stories to tell, and after 60 years of directing and animating, Hastrup does not have it in him to stop just yet.

Portrait by Christian Monggaard

Translated by Başak Yılmaz

Photos by Kim Wendt

Two childhood experiences, in particular, made their mark on animator and film director Jannik Hastrup’s (b. 1941) shaping into a storyteller: Charlie Chaplin’s The Gold Rush (1925), which was the first movie he ever saw, and a theater production of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The Gold Rush made a big impression on him, not because it was the funniest thing he had ever seen, but because he could not grasp the reaction of the adults in the audience. In one particular scene, Chaplin’s gold-digging friend, Big Jim, is so starved that he begins to hallucinate that Chaplin is a chicken. Hastrup’s parents laughed at the scene – his father nearly died from laughing, he tells – but the little boy could not detect what was so funny about this scene. He felt bad for Chaplin, and the adults’ reaction did not sit right with him.

At the age of six or seven, Jannik Hastrup went to the theatre in Copenhagen – he lived in rural Zealand with his family – to see Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Emil Christoffersen was playing the lead role of Uncle Tom in black face, and to Hastrup, “it made a brutal impression when they whipped him. He was not actually struck, but I could not see that from the fifth or sixth row. Those two experiences have left their mark.”

The marks take the form of indignation and humanism which flows throughout the entirety of the unique body of work that 80-year-old Jannik Hastrup has spent the last 60 years molding. A body of work that renders him the grande, most important, and most productive figure in Danish animation ever. He stands with the outcast, the weak and quiet existences in life, and to put it very simply, all of his many films, of which most are targeted at children – from Circleen (Cirkeline, ed.) and Benny’s Bathtub (1971) to Samson and Sally (1984), War of the Birds (1990), and A Tale of Two Mozzies (2007) – revolve around the same message: be kind to others.

The indignation is alive and kicking, I realize when we are sitting across from each other in his lovely house in Copenhagen to talk about his life and career.

“It keeps bothering me about the women and children in Syria. How the hell can it take this long to bring them home? The indignation of the way we treat, what we call the third world, the developing countries,” he says.

– This indignation has been a driving force …

“Yes, and it still is. And it is not unlikely that a few more Circleen shorts will see the light of day.”

In reality, Jannik Hastrup is retired, but, as he says: “For 60 years I have moved cardboard pieces around. I don’t know what it’s like not to work. I am fortunate to have my garden where I can spend a lot of time, but the long winters puts a limit to it. For my entire life, getting up and going to work has been a holding point.”

Animator by accident

Jannik Hastrup never set out to become an animator. Rather, it was something that he ‘sidled up to’, as he likes to phrase it. At one point in his life, when he was young, he wanted to be an architect, but he also played jazz music, the trumpet, and he had a fascination with cartoons. The latter sealed his destiny, not least because of how successful he was with the medium. He taught himself how to draw cartoons, with the help of old Disney collecting albums published by the popular coffee substitute company Rich’s. On the last page of these albums, there was an insight into the craft of animation. In collaboration with his wife at the time, Hanne Hastrup, who was an illustrator, he made an 8 mm film titled The History of Jazz. He showcased the film to producer and cartoon pioneer Bent Barfod in the hopes that Barfod could teach him a few tricks.

This led to an apprenticeship with Barfod, which, for Hastrup who already had a family to support, was perfect timing. Around the same time, approximately in 1960, Flemming Quist Møller joined the team, and the two young men quickly grew close, playing music together and making films. Throughout the 1960s, Hastrup and Quist Møller both learned the animation craft by working together on an array of short films and commercials. The projects often paid well and encouraged the artists to produce 10 second long commercials.

“He was the designer, I was the animator,” he says about the collaboration with Quist Møller. Hastrup began directing his own cartoon shorts, some funded by Statens Filmcentral, and little by little he was so occupied with work that he had to put the music on hold.

By the end of the 1960s, Hanne Hastrup came up with Circleen, Ingolf, and Frederik, the little ivory-haired girl, and her two rodent friends – the trio starred in 19 animated shorts paid and broadcast by DR (the Danish Broadcasting Corporation, ed.) in the years 1967-71. Early on, Jannik Hastrup and Flemming Quist Møller knew that they would never receive enough funds to do a cartoon the Disney way, especially since it was only broadcast on TV. When they knew what their budget looked like for a certain production, they would do the math backward to make sure they could survive.

“It wasn’t a very well-paid gig, so we took it on as a challenge,” Jannik Hastrup says. “Instead of explaining how it would cost 100,000 Danish kroner to produce one minute of a cartoon, we presented this amount as our living costs, and then we had three weeks to make a Circleen film.”

He laughs.

Our work vibe was very jazzy and improvised. For the first Circleen films I didn’t even use a storyboard.

– Jannik Hastup

Time-saving cutouts

To meet their deadlines, Jannik Hastrup, Hanne Hastrup – who made the backgrounds for the films -, and the rest of the film crew would work around the clock using the stop-motion technique known as cutout animation. They would cut out the characters and move the card around on the background, saving valuable time, since they didn’t have to produce the traditional 12-24 drawings per second.

“If the story was good enough, the technique and the appearance were secondary. There is a certain charm and spontaneity to cutout-style animation, a tactility to it. You see that it is cardboard pieces. We never tried to cover that,” Jannik Hastrup says, calling the Circleen movies a Dogme film of sorts, where the limitations of the film are turned into its strength. He was right. The films were a success with the young target audience, a success that to this day brings Jannik Hastrup royalties and a success that some 30 years later turned into three feature-length films starring Circleen and her friends.

Jannik Hastrup remembers how the script to a Circleen short was no more than five-six pages and consisted mainly of lines.

“It barely said what the characters did,” he recalls.

“‘Frederik goes out in the garden,’ or ‘they all go outside’. Our work vibe was very jazzy and improvised. For the first Circleen films I didn’t even use a storyboard. We were a studio of five or six people, and the ones animating the film were constantly bent over the table, and you knew not to crack any jokes because it could throw them off.”

The deep concentration and discipline was in part the result of economic pressure on the production, and in turn, the animation gig became a very lonesome, all-consuming job.

At the same time, it was important that the stories in these films were told at eye level and that they were in solidarity with the children that the films were targeted at – who also voiced the characters. It isn’t so much the indignation as the humanism that is reflected in Circleen. Little Circleen is usually the reasonable and responsible one, while Ingolf and Frederik are the ones causing mischief when the trio embarks on an adventure.

“Not that it was something to brag about, but we could recall what it was like to be five years old and have the adults run the show,” Jannik Hastrup says, mentioning the late Mogens Vemmer, the head of DR’s B&U (children and youth department, ed.) at the time. Vemmer, who ordered the Circleen films from Hastrup and his studio, shared Hastrup’s philosophy that his shows should address the target audience very directly.

Fame and fortune

In 1971 Jannik Hastrup and Flemming Quist Møller made Benny’s Bathtub – to this day one of their most cherished and seen films and an entry in the Danish Culture Canon. Originally, Hastrup and Møller wanted to adapt Flemming Quist Møller’s children’s book Cykelmyggen Egon (1967), but due to the characters’ thin mosquito features, it was not possible to render them as cutouts. Instead, it would have had to be made more traditionally in cel animation, and this exceeded DR’s budget. And so almost 40 years would pass before the pair finally brought Egon to the screen with A Tale of Two Mozzies in 2007.

Flemming Quist Møller conceived the story for the 41-minute-long Benny’s Bathtub on a trip to Turkey. This was the story of the boy Benny, who lives with his mother in a mundane residential area, and discovers a world full of adventure at the bottom of his bathtub. The film, made in cel animation, is a charming, inventive, and musical tribute to imagination, and it has a slightly rough and draft-like mark because that is how the two directors wanted it.

“We wanted to steer clear of the neat, and we wanted you to see that it was painted by hand,” Jannik Hastrup says and continues to talk about how they both thought that the film was going to be their ticket to fame and fortune. That didn’t quite happen, and although the film did well in the cinemas and received rave reviews, it was still difficult for them to raise money for future projects, and the film was Hastrup and Møller’s last collaboration for many years.

The financial aspect has always been an important driving force for the director. It was important for him to be able to provide for his family, and at the same time, he – alongside Flemming Quist Møller – had learned a lesson by watching Bent Barfod. The producer also wanted to make the fiction films of his dreams, but he was forced to make commercials to keep ends meeting in his company with a large house, quite a lot of employees, and expensive equipment.

“His commercials were of great quality, but he never had a respite after finishing a film, a chance to ask himself, ‘What should we make next?’ the way Flemming and I had. After the feature films and tv series, we were exhausted. Marie Bro, my partner at Dansk Tegnefilm, always made it a priority to ensure that there was enough money to cool down for three months after finishing a project. This way we were never forced to make a commercial for financial reasons,” says Jannik Hastrup, who made it a virtue to stay within budget at all times.

At the same time, he was, and remains, a restless man with little patience for the bureaucratic process when applying for funds. When Jannik Hastrup has an idea, he wants to get the wheels turning and realize his vision, not wait for some consultant at Statens Filmcentral or The Danish Film Institute or an editor at DR to assess his project. In the early days, seeking funds was a quick ordeal and you could submit a four-sentence synopsis to successfully apply. The field was not run over by applicants either. But over time, funding and application systems became more bureaucratic and slow.

“Sometimes the process would take months, so I would simply start making the films before we even had the funding,” Jannik Hastrup says.

“I always did that. And often it was the source of conflict between me and the producer or my partner Marie Bro. Marie preferred everything to be in order beforehand, but from the moment I had an idea, like with War of the Birds, I sat down and began drawing.”

The US out of Vietnam

In the 1970s, Jannik Hastrup was politically involved, and his position was quite leftist but he didn’t choose sides with any political party – he tells with a laugh about the time in the late 1960s where he painted in big, red letters the words ‘USA out of Vietnam’ on his outhouse. His political involvement was reflected in two large and quite controversial cartoon series based on Swedish books: Historiebogen (The History Book, ed.), which told the problematic story of Europe’s relation to Africa from the Middle Ages onwards – not least the triangular trade in slaves made a big impact on Jannik Hastrup -, and Sven Wernström’s multi-volume work, Trællene (The Thralls, ed.), on slavery in Scandinavia from the year 1000 until 1900.

Neither of the two series was shown on Danish television – they were deemed too political and would have caused a stir, not least with the politician Erhard Jakobsen, who liked to go on about the leftist radicals at the Danish Broadcasting Company. The Thralls aired on Swedish television, but only after some of the more violent scenes were cut. Both series were made available in Denmark through Statens Filmcentral and were shown at schools nationwide.

In the early 1980s, Jannik Hastrup paired up creatively with another politically and socially engaged figure, the children’s book author Bent Haller, and over the following 20 years the two – Haller as a screenwriter – worked together on a wide range of cartoons, which dealt with major important issues such as pollution, war, and racism. The duo’s first film, Samson and Sally (1984), was also Jannik Hastrup’s first feature film, followed by Subway to Paradise (1987), War of the Birds (1990), The Monkeys and the Secret Weapon (1995), HC Andersen and The Long Shadow (1998), and The Boy Who Wanted to Be a Bear (2002), several of them based on books by Haller.

“Not least in the years with Bent Haller, I had a desire to get involved,” says Jannik Hastrup, about the entertaining, poetic, dramatic, and political films, which were at the same time more expensive than his earliest productions, and which challenged him artistically and visually to try out new techniques and processes.

Digitized cutout animation

And that brings us back to the indignation and the short Circleen film that Jannik Hastrup plans to make because he cannot help it – and because it is cheap and straightforward. It is another cutout animation, but the figures, which are still hand-drawn and cut out of cardboard, have been digitized so that he can use a computer now to move them around, which also means that he can almost just make the film himself. It was the same technique he has used on the feature film editions of Circleen, the most recent in 2018, and which he and Flemming Quist Møller used on the two Cykelmyggen films they made together in 2007 and 2014.

“It is not many days ago that I found out that I might need to make one more Circleen film. About a refugee who comes here, but without using the word ‘refugee’,” he says.

The story is inspired by a ten-minute animated documentary, Ignoranterne, made by the director a few years ago, in which a boatload of refugees capsizes and they all drown. A lifeless little girl and her teddy bear are washed up on the beach in front of some tourists, who sit under their umbrellas and watch passively.

“I try to combine that with Circleen. The little teddy bear is a rabbit, and Ingolf walks by, thinking at first that the rabbit has drowned. Then he pulls her up on the beach and she wakes up but speaks a language that no one understands. Ingolf has to guess what she is saying and he stops her as she wants to go out into the water again. She wants to go out there, to where the child that owns her is. This is the beginning of a story that I do not know if it will turn into anything.”

And it is a film where Jannik Hastrup, as so often before in his career, reacts to the world and the things that happen in it, without trying to hide the harsh realities and make happy conclusions, even though he addresses children.

We wanted to steer clear of the neat, and we wanted you to see that it was painted by hand

– Jannik Hastup

Children’s films are important

“I firmly believe children’s movies are one of the most important things to make. Good children’s films, mind you, because so much shit is made,” says Jannik Hastrup. He has always admired the abilities and craftsmanship of Disney animators, but he is not necessarily as enthusiastic about the stories they tell – although Bambi (David Hand, 1942) made an impact on him when as a boy, which inspired the death of the mother in Samson and Sally.

“I’ve always said that Disney did to the US what Goebbels did to Germany,” he says with a wry smile.

“Of course, that’s roughly speaking, and I have enjoyed my fair share of Disney movies, but it is vital to give the kids some good attitudes. Not that I want to indoctrinate anyone, but one has to behave properly. For instance, Circleen, Ingolf, and Frederik do not use swear words at all. One can identify with Circleen because she is never the naughty one. She is wholesome. She is the matchbox that you measure yourself against, both in size and mentally. The two boy mice are the naughty ones. If Circleen made trouble, there would be nothing left. I’m deeply moved every time someone hears my name and says, ‘My goodness, is it you who made Circleen?’ It’s touching when people say the stories and characters were a cornerstone of their childhood.”

It is in such moments that Jannik Hastrup is reminded of how much his film has meant to the people who have seen them. And this is something he occasionally needs to be reminded of, not least in a world so full of inequality and injustice, and where he may well get the idea that he would have done more good as a doctor or nurse.

“It’s a little poor not to have tried one’s hand at something else at any point in life,” he says, still emphasizing that he is not one to regret.

“But when faced with God one day, he will inevitably say, ‘Is that all you have done?’”

He laughs.

Collaborators

WeAnimate Magazine is dedicated to all the people who animate and make things, lines, and ideas come to life.

WeAnimate ApS is founded and owned by The Danish Animation Society (ANIS) www.anis.nu

Tell us what you think? Tell us at hello@weanimate.dk | #weanimate | our Privacy Policy