Casting the Building Blocks for Dreams and Stories for Three Decades

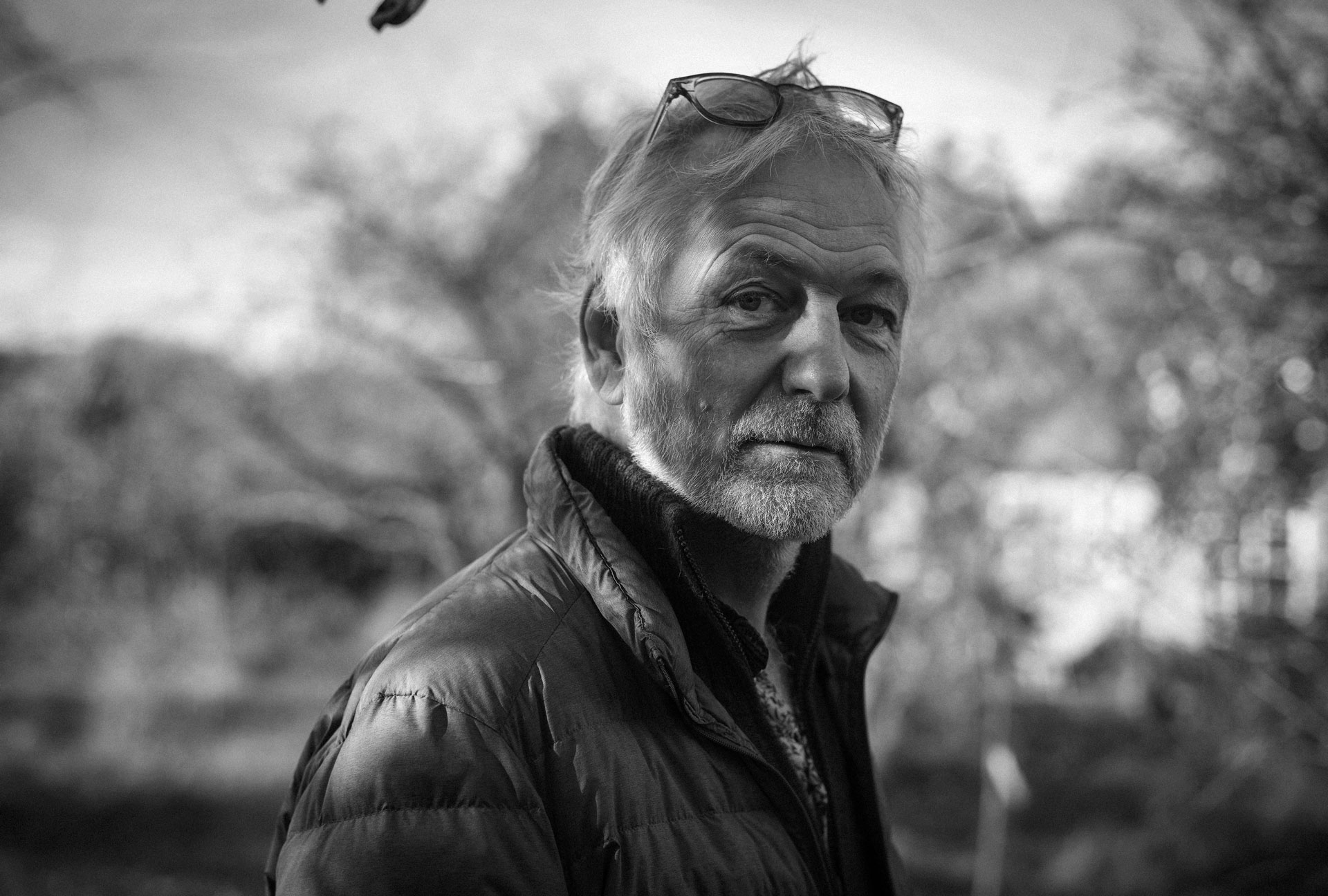

A Conversation with The Animation Workshop’s Founder Morten Thorning

WeAnimate 2023-12-04 | wam#0023

In the Danish region of Jutland exists a type of personality, which is described as ‘lun’. The word literally translates to lukewarm, but the connotation in Jutland is a type of person who always tries to maintain a good mood. Not by cracking jokes, but rather by telling things with an underlying touch of very dry humor and slightly poking fun at people.

Morten Thorning is the epitome of ‘lun’ when I meet him on a dark October evening. He is in a great mood, smiling through our entire conversation, never afraid to see the humorous aspects of his illustrious career and the people he interacted with through the years. While there is something very Jutlandish and anti-metropolitan about his personality, his actual body of work is very cosmopolitan. As we talk he ends up having mapped out a wide network of people from all over the world.

In this sense, Thorning can be seen as a direct reflection of The Animation Workshop (TAW), the institute he founded and drove for 31 years (even though Morten says it was 62 years, as he worked double time the whole time). It is a school located in the middle of Jutland, an institution that he wishes “the entire international animation community should feel a sense of ownership of”. It is also the achievements from TAW that were the basis for the jury’s decision to grant him the Lifetime Achievement Award at the 2021 installation of Fredrikstad Animation Festival in Norway. Therefore, the story of Morten Thorning is evidently also the story of TAW, so let’s start where it all began.

FROM CHAOS TO PROFESSIONALISM

The beginning of The Animation Workshop is a chaotic story of local government failures, where an unlikely chain of events resulted in the city of Viborg having a huge unfinished center for squash which they didn’t know what to do with. Thus, the first building to house the future Animation Workshop was born. Then in the 1980s regional TV stations became a thing, and in an effort to land the prominent TV station in Viborg, a media education center was built. Unfortunately, they were surpassed by the town of Holstebro — according to Thorning because they had a better lake view.

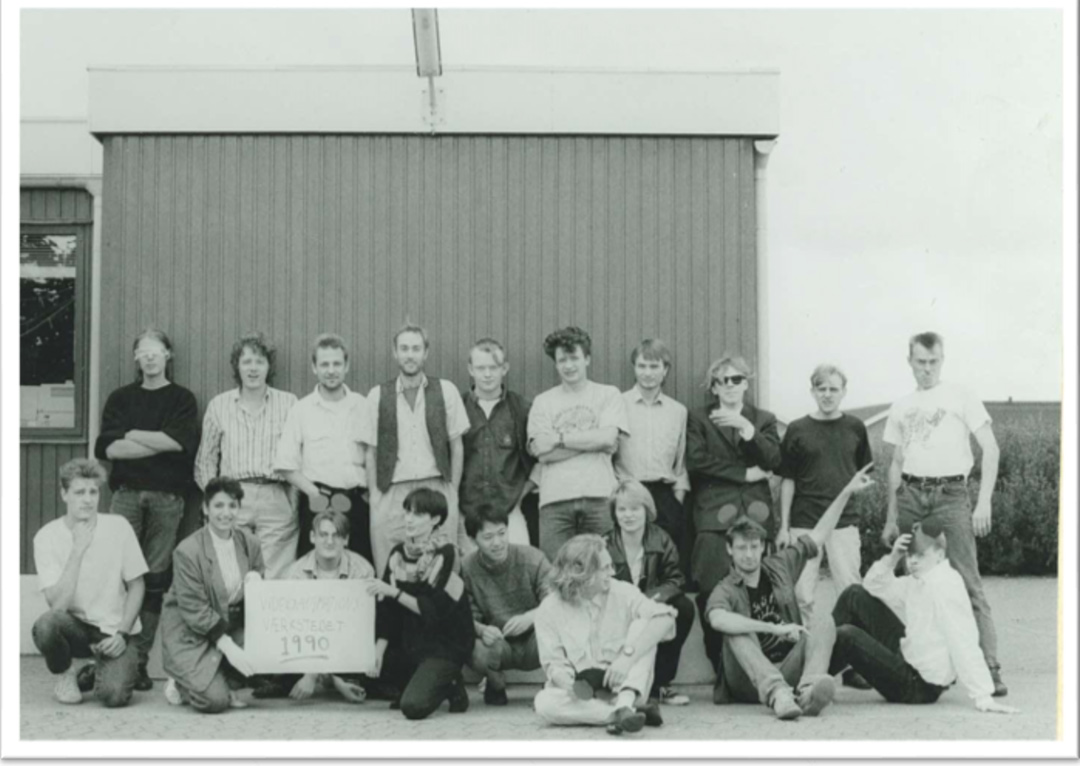

This is where Morten Thorning enters the scene, and the birth of The Animation Workshop takes place. It was originally conceived as an unemployment project, where people could come and learn the ropes of animation instead of digging ditches. Thorning’s idea was to create a creative ‘højskole’ (an independent school offering non-formal education for adults, ed.), where you could nurture a close-knit community with your fellow students. In the beginning, it attracted the local artistic community, which was a group of individuals who went on to have successful careers . The project quickly became so popular that it began to attract unemployed people from the neighboring towns and municipalities — which wasn’t exactly what Viborg had planned, but they luckily were followed by economic compensations.

From the early days, TAW produced significant results. They first got international attention in an MTV contest with the ecological short film ‘The Solution ‘ (1991), where the animals trick all the humans to leave the earth that they had been destroying. TAW got the attention of the officials at Viborg Municipality, who in return ensured a better and better financial foundation for the school.

Simultaneously, the European animation society was pushing against the commercial style of animation coming from the United States, both ideologically and stylistically. Numerous things caused this, but one of the major factors was a law from the European Parliament that forced TV stations to show at least 50 percent European-produced content. Another factor was the creation of the European support-program MEDIA.

This was to make sure Europe was not culturally dominated by American culture. Thorning took a unique stance towards the American animation style: “I said, ‘No! We need to learn how to make animation look slick and great, and the Americans already figured that out 70 years ago when Walt Disney sat down and spent millions on figuring out how to create motions that make people absorb the stories. So we should learn how to tell the stories from the Americans, but we should tell our own stories'”. Thorning’s position was simply that if they couldn’t make animation that looked great, they would always lose the battle when families had to decide whether to tune the TV into a Danish animation film or one produced by Disney. He notes that it was a move that should be seen in the context of its time. These days commercial animation is no longer dominated solely by Disney. Thorning highlights Japanese anime in particular as a great addition to the idea of animation amongst the population at large. Specifically, the Japanese’s courage to tackle the darker, but also very human, aspects of life is something that was missing in the American animated storytelling.

To make sure that the students learned these styles, a big part of Thorning’s work was to hire the best-suited teachers for the job. At the time, Disney’s techniques were strictly encapsulated amongst the studio’s own animators. However, news traveled to Thorning that the animator Richard Williams, friends with Mit Kahl (one of Disney’s Nine Old Men), had escaped to an island in Canada after his project ‘The Thief and the Cobbler’ had bankrupted him. Thorning got hold of Williams, and they managed to get him to do a series of masterclasses in Denmark. Now TAW had a direct source for the Disney techniques (these Masterclasses later spawned the much popular book ‘The Animator’s Survival Kit’.)

Williams made it clear from the get-go that the school needed to teach the students to draw better — a fair critique, says Thorning, “because Danes stop drawing when they enter the third or fourth year of elementary school”. To solve the issue, they invited the young professor Artem Alexeev and his Russian network from Saint Petersburg to create The Drawing Academy.

Over the next 7-8 years or so, the school began to attract a mass of talent that could not be ignored by the rest of the Danish media industry. The turning point came with the acknowledgment from the National Danish Film School, when Gunnar Wille, the leader of the animation director education, said, “You will make the animators, and we will make the animator directors”. A stamp of approval that proved useful later, when handling politicians. But it did take some time for the rest of Denmark to recognize that Thorning’s — in his own words — “idiotic and naïve idea that something this creative could happen in Jutland” really settled in the minds of the Copenhagen-oriented media business. Thorning cannot contain himself in laughter, saying: “It is a total coincidence that the Capitol is Copenhagen. It only made sense, when we administrated Sweden, and since we don’t do that anymore, shouldn’t we move it back to Jutland?”

The Animation Workshop had now grown to be a nationally recognized institution with international collaborations, but it was still officially an unemployment project. This all changed soon.

A BONAFIDE INSTITUTION ENTERS THE RING

In the early 2000s, things started to change in Denmark. A major shift happened when Danish film producer Peter Aalbæk (Zentropa) joined the social democratic party, spearheading a movement that convinced the government to create a much stronger Film Institute. The public budget went up from 150 million DKK to 400 million DKK a year — a clear sign that Danish cultural policy did not only want to support theatre, ballet, and opera, which Thorning teasingly says, “might be a little anachronistic these days”. A little part of the new budget was used to create film workshops all over Denmark, but at the time, nobody really wanted to have anything to do with animation. Once again, Viborg consolidated its position as the animation capital, even further.

In late 2001 the government shifted in Denmark, towards the neoliberal party Venstre. Thorning, who says that at heart he is probably left-leaning, managed to foresee the worst scenario of budget cuts, only to witness the contrary. The new minister of education, Ulla Tørnæs, wanted to create more bachelor educations in Western Denmark and approved The Animation Workshop’s accreditation as an official educational institution. Reflecting on this period, Thorning says: “What really changed things in the years 2000-2003, was the combination of it all. Having a workshop with the proper equipment, and having an official education created a magnificent collaboration between knowledge, skills, ideas, art, and technology that really pushed everything forward”.

Getting support on a national level and not only from a municipality was very important for the school. After the millennium animation became increasingly more reliant on continuously more powerful (and expensive) technical equipment. The new era needed to be reflected in the education: “When you are making a movie with a budget of 50 million DKK, you need to be certain that the people you hire have been through the different aspects from shading, character animation, and some production management, which they write in their CV, on a sufficient level,” Thorning explains. It is a change in the nature of the animator, from the one-man-band approach of ‘La Linea’ to the multi-specialized productions of present-day animation studios. The change also reflected back on the experience of the students at TAW. Thorning continues: “They need to constantly make choices like, do you want to be a modeler, a 2D-animator, character designer, layouter, storyboarder, or can’t you be bothered to draw anymore and instead want to be the one in charge of steering the productions, or maybe you want to direct because your ideas are great, and so on”.

Besides the political and financial support, the early aughts were also the years where international collaborations started to expand rapidly, with the lecture- and workshop-based training programme Animation Sans Frontières being of exceptional importance: “Being part of Animation Sans Frontières put us in a European network of the absolute best. There is a myriad of movies and productions that emerged from the students at the different schools visiting each other. For instance, [Danish animation studio] Sun Creature, comes from this network,” Thorning says. In many ways, the ADF movement is an international extension of Thorning’s idea of community being at the core of how he wanted The Animation Workshop to operate.

NOT JUST FOR THE MIND BUT ALSO FOR COMMUNICATION

In 2009 the Animation Hub came to be. Animation Hub was an innovation network that used animation in a myriad of fields that helped communicate information. One of their early ideas was to animate news, “but sadly the process took so long that once the animation was done, it wasn’t news anymore,” Thorning says. They did, however, entertain the idea to the extent that they met with a Taiwanese studio, where 20 people stood ready in front of a blue screen to motion capture today’s news. Thorning recalls: “It was fascinating, but their main business was reconstructing traffic accidents and killings. The news that were animated were generally very sad, so in reality it wasn’t that fun”.

However, two really big movements emerged from Animation Hub. The first one being ANIDOX, spearheaded by directors Uri and Michelle Kranot. ANIDOX:LAB became an international development lab, pairing animator directors with producers and directors who wanted to develop documentary films. “You could use animation to visualize whatever the camera can’t film,” Thorning explains. An example of this collaboration is the Danish director Jonas Poher Rasmussen, who discovered how powerful a tool animation truly is through ANIDOX:LAB. Something he has taken to impressive heights with the movie ‘Flee’ (2021), which is this year’s Danish candidate at the Academy Awards.

The other impactful movement, coming out of Animation Hub was Sci-Vi. The Sci-Vi movement allows the more artistic animation directors to develop their storytelling skills working together with scientists and science institutions from all over the world. “I think that Sci-Vi really is making complex science much easier to understand. And much more fun to watch,” Thorning muses.

Today The Animation Workshop is a Center for Animation, Visualization and Digital Storytelling, with a multifaceted R&D Department, aiming to develop animation and digital arts to new potentials of the future.

A STORYTELLER AT HEART

Having grown The Animation Workshop from an almost anarchistic ‘højskole’ to a deeply professional and internationally connected education, teaching students how to use animation not only for cartoons and fantasy but rather as a tool in a myriad of industries, Thorning left TAW in 2019. After having worked there for 31 years (sorry, 62 years!) Thorning started to focus on himself for a change: “I needed to reinvent my own self-image, and what I discovered was that I am a storyteller at heart”. One of the stories that Thorning is currently finishing up, is a first draft on a large European animated drama series: “When I see what is being internationally produced, I see productions that are beautiful, but they want to either entertain me or scare me. It is not stuff that binds us together, and it is important for us to stand together. Humans as a species have never faced challenges this massive before, which demands that we can act in unity”. This is at the heart of everything Thorning has done. He wants to bind the province and the metropolitan together. He wants to bind animation together with other industries, and he connected TAW to the entire world.

When we are finishing up the interview, Thorning tells me that he’s also working with VR with the new White Hole Theater, and as a final ‘lun’ comment says with a smile that maybe theatre doesn’t have to be so anachronistic after all.

I feel a deep gratitude to everybody, from the fantastic employees in Viborg to the people of the global animation community, who believed in the story and the idea of The Animation Workshop. I might have dreamt up that story, but it was You, showing your support by expressing your belief in the story, and taking advantage of it, that made the dream possible.

Morten Thorning

Credits

Words: Rasmus Riegels

Collaborators

WeAnimate Magazine is dedicated to all the people who animate and make things, lines, and ideas come to life.

WeAnimate ApS is founded and owned by The Danish Animation Society (ANIS) www.anis.nu

Tell us what you think? Tell us at hello@weanimate.dk | #weanimate | our Privacy Policy